Photo: NCLA client Lisa Milice and her baby

As I have recently found out, there are many things to worry about as a new or expecting parent. The joy of welcoming a new life into the world can easily be eclipsed by a wide range of concerns. Not to mention, the nearly herculean task of not following the siren call of an entire baby product industry that preys on parental anxiety.

At the end of the day, for many new and expecting parents like myself, there is one concern we go back to. “Is this safe for my child?”

I incorrectly assumed that the answer to that question was a simple “yes” or “no.” But the answer is more complicated than that. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has mandatory safety rules and standards for some 25 so-called durable infant and toddler products, which include everything from cribs to infant carriers.

But these safety standards—despite being the law—are not readily accessible as they are locked behind a paywall of a private organization, ASTM International. How can the law be hidden? More easily than you can imagine. The CPSC and other agencies use a regulatory practice called “incorporation by reference” that allegedly permits an agency to outsource the development of standards to be incorporated into a final rule or regulation.

NCLA is currently challenging CPSC’s use of incorporation by reference on behalf of our client, Lisa Milice, who like me, just wanted to know if the product she was purchasing for her baby was safe. Last week, I eagerly watched NCLA’s “Hiding Behind a Paywall” Lunch & Law where my colleague, Jared McClain, spoke with Professor Nina Mendelson of the University of Michigan Law School and Adina Rosenbaum of Public Citizen Litigation Group about the Milice case and the problems that arise when the government puts laws and regulations behind a paywall.

Later that night, as my husband and I unpacked our convertible bassinet and travel crib, I was greeted with some now-familiar words: “This product complies with ASTM F2194-13” and “This product complies with ASTM F406-19.” Turns out our combination bassinet and crib was not one, but two durable infant products. I checked the cost to view the standards, $151 for both or roughly the average price of this type of product. Thank goodness I did not buy the combination bassinet, pack-and-play, and changing station. It would be three durable infant products and cost $209 to view all standards that apply—more than the product itself.

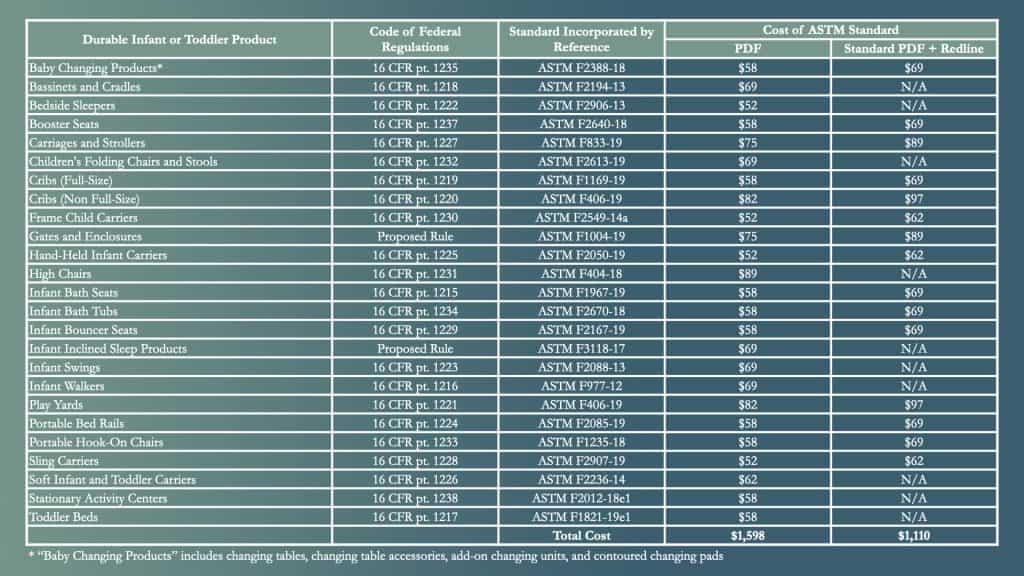

This got me thinking, how much would it cost to view all the durable infant and toddler product standards—which, again, are the law—that may impact my purchasing decisions over the first years of my child’s life? As the chart below shows, $1,598.

The total cost to view the all 25 standards is two to three times more than the cost of diapers for a year, nearly twice the national average cost for a month of daycare, or about 12% of the total cost of raising a child in their first year.

And the calculation above does not include many items parents purchase that also incorporate standards by reference—infant toys and pacifiers to name a couple. For instance, pacifiers are subject to both the U.S. Toy Standard and standards regarding levels of certain carcinogens in rubber pacifiers. The latter of which is incorporated by reference in the U.S. Toy Standard, or as I prefer to think of it, incorporation by inception. As with the others, these standards for pacifiers do not come cheap either, running $157 total for the two or roughly 26 times the cost of a rubber pacifier. Moreover, it is not even clear that the carcinogen standard is still in effect, as ASTM’s standard was withdrawn in 2020. But there is no way to check this without purchasing and reviewing the standards.

The price to access the law is too high. But as NCLA argued in its opening brief in the Milice case, the CPSC’s failure to make certain standards freely accessible to the public also violates the Constitution of the United States, the CPSC’s organic statute (i.e., the statute that created the CPSC), and the Freedom of Information Act. The public has a right to know what the law is, and consumers make better purchasing decisions when they know what standards apply. Right now, the CPSC is stopping either from happening. As Chief Justice Roberts recently declared, “no one can own the law.” It is time for the courts to recognize that principle for CPSC’s standards as well.