Big Cases by the Numbers [December 30, 2024]

While quantifying case importance is a subjective art at best, there are some measurable elements that provide deeper than a gut impression as a basis for comparison. Some possibilities include dollar value or companies involved, case complexity, differences of opinion between judges, firms involved in litigating the cases, and interests or implications for those beyond the immediate parties to the matter.

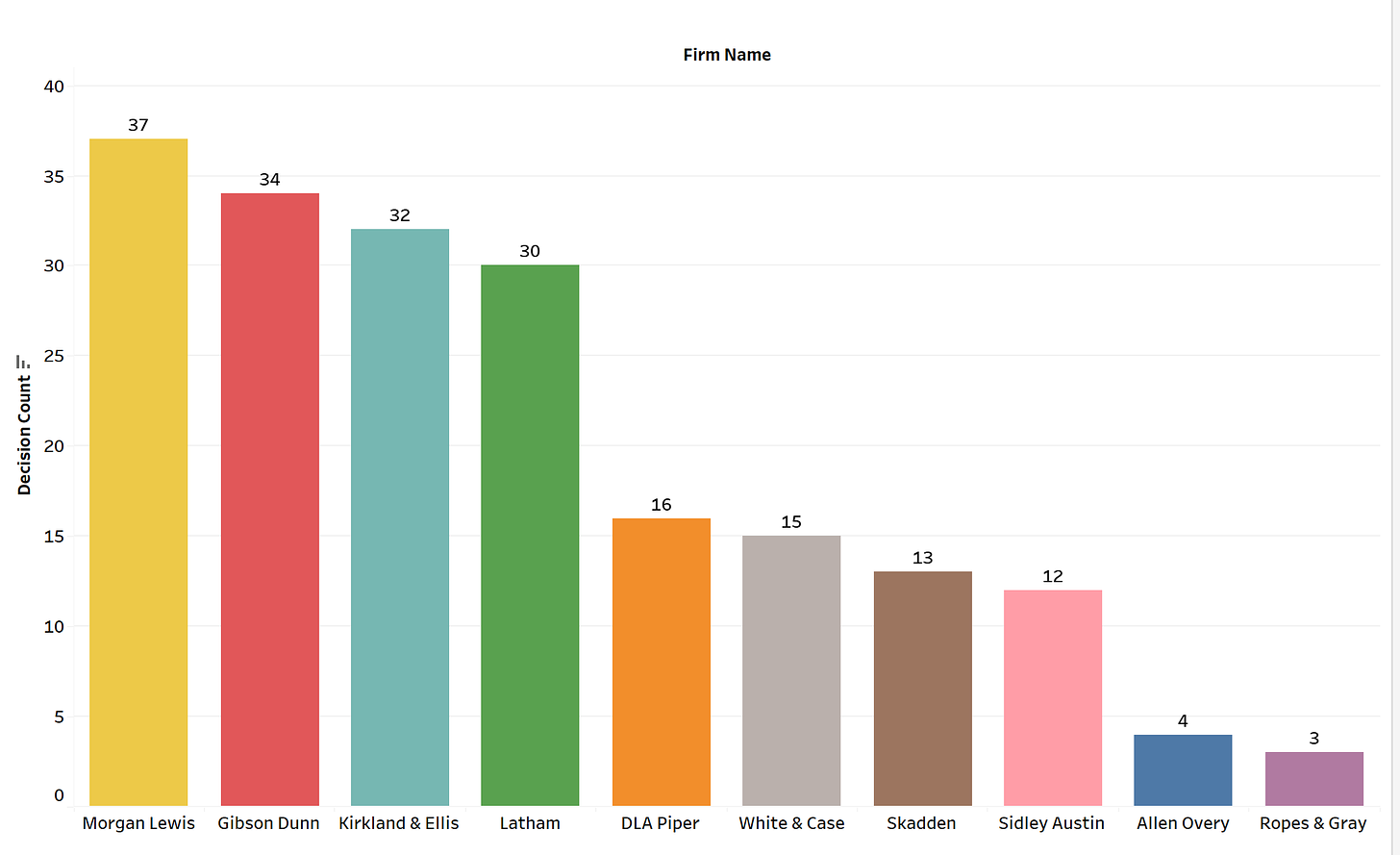

With these layers in mind, I started out by examining opinions where the following firms which are currently around the top revenue generators in U.S. law were counsel: Gibson Dunn, Skadden, Latham, Morgan Lewis, White & Case, Ropes & Gray, Allen Overy, Kirkland & Ellis, DLA Piper, and Sidley Austin.

The sample of written opinions with at least 100 words (a way to attempt to exclude summary decisions) based on these parameters was 136.

Here are a few ways to break down the numbers. First based on law firm

There is quite a range from 37 to three decisions and large drops from the first four firms to the next four and finally to the last two.

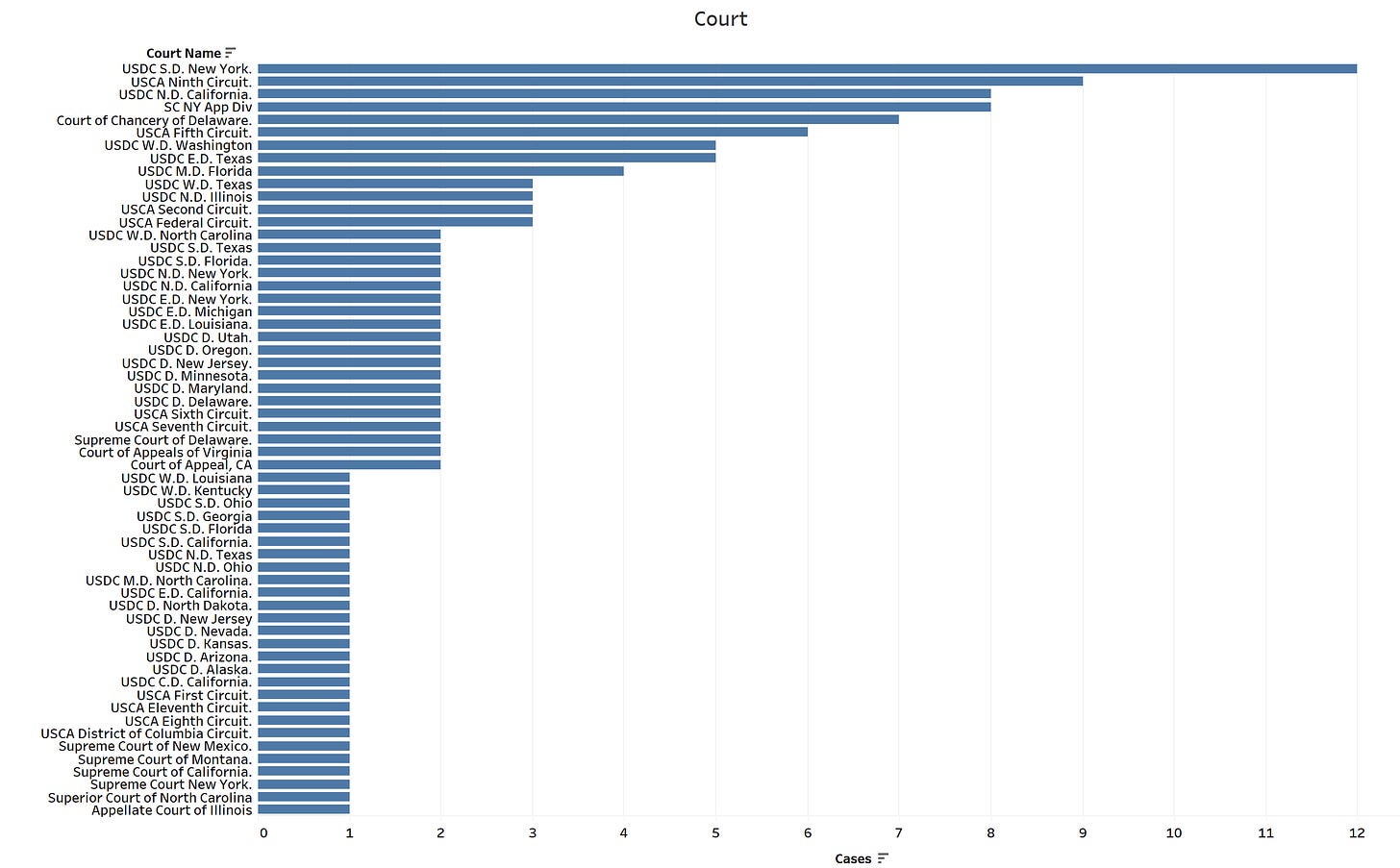

To get a sense of the lay of the land, below are the courts that issued these opinions.

Here we see the impact of the coasts as the four courts with the most decisions are SDNY (New York), NDCA (California), the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (west coast), and the appellate divisions of the New York Supreme Court (the intermediate appeals tribunal in New York).

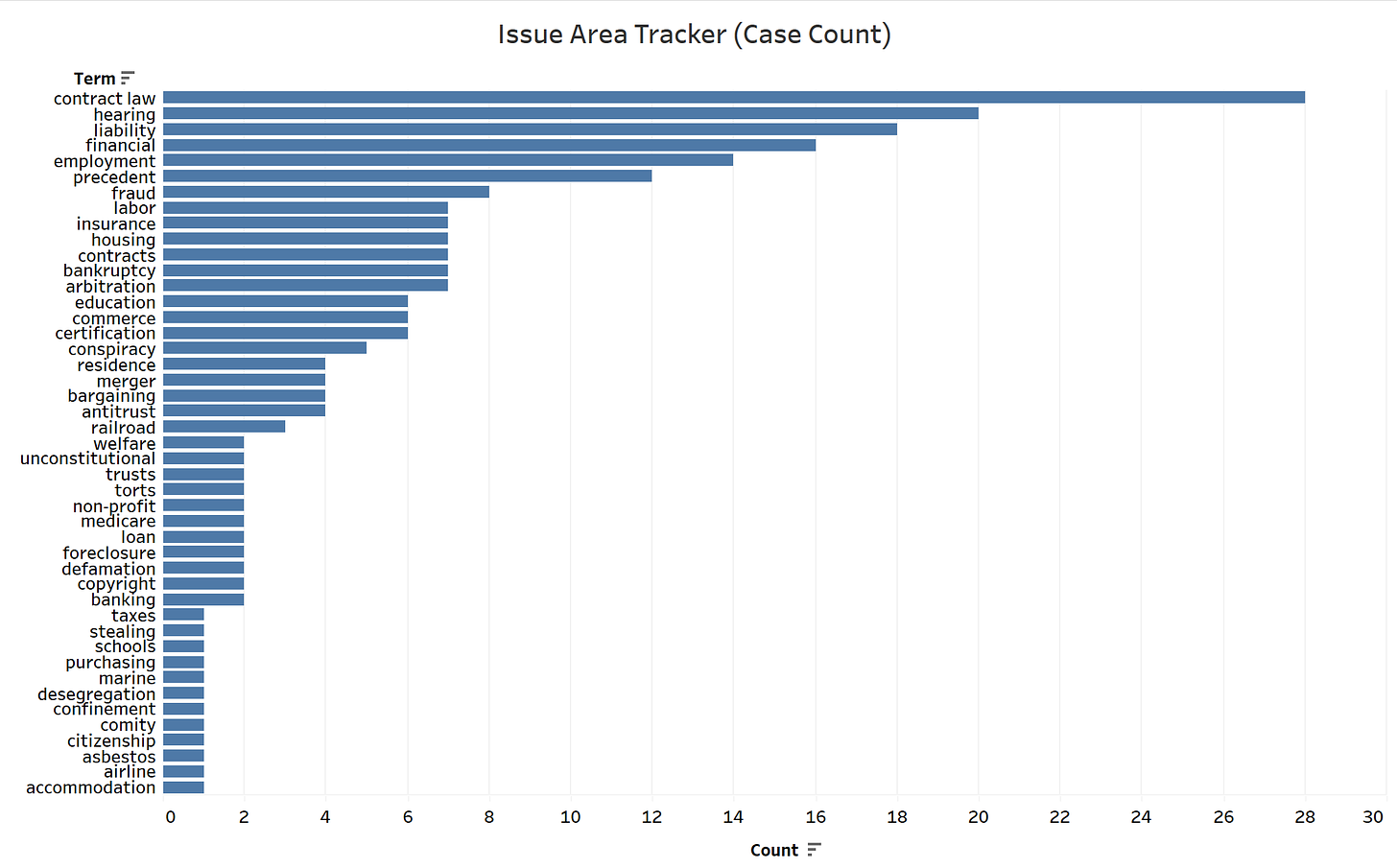

Next is a quick way to break down some of the significant issues in the cases based on a dictionary approach looking for multiple times these terms arise in a decision.

Many of these cases (perhaps not surprisingly for big firms) deal with financial implications and deals that broke down. There are still a nontrivial number of cases where the immediate concerns are not financial or at least are not predicated only on business interests.

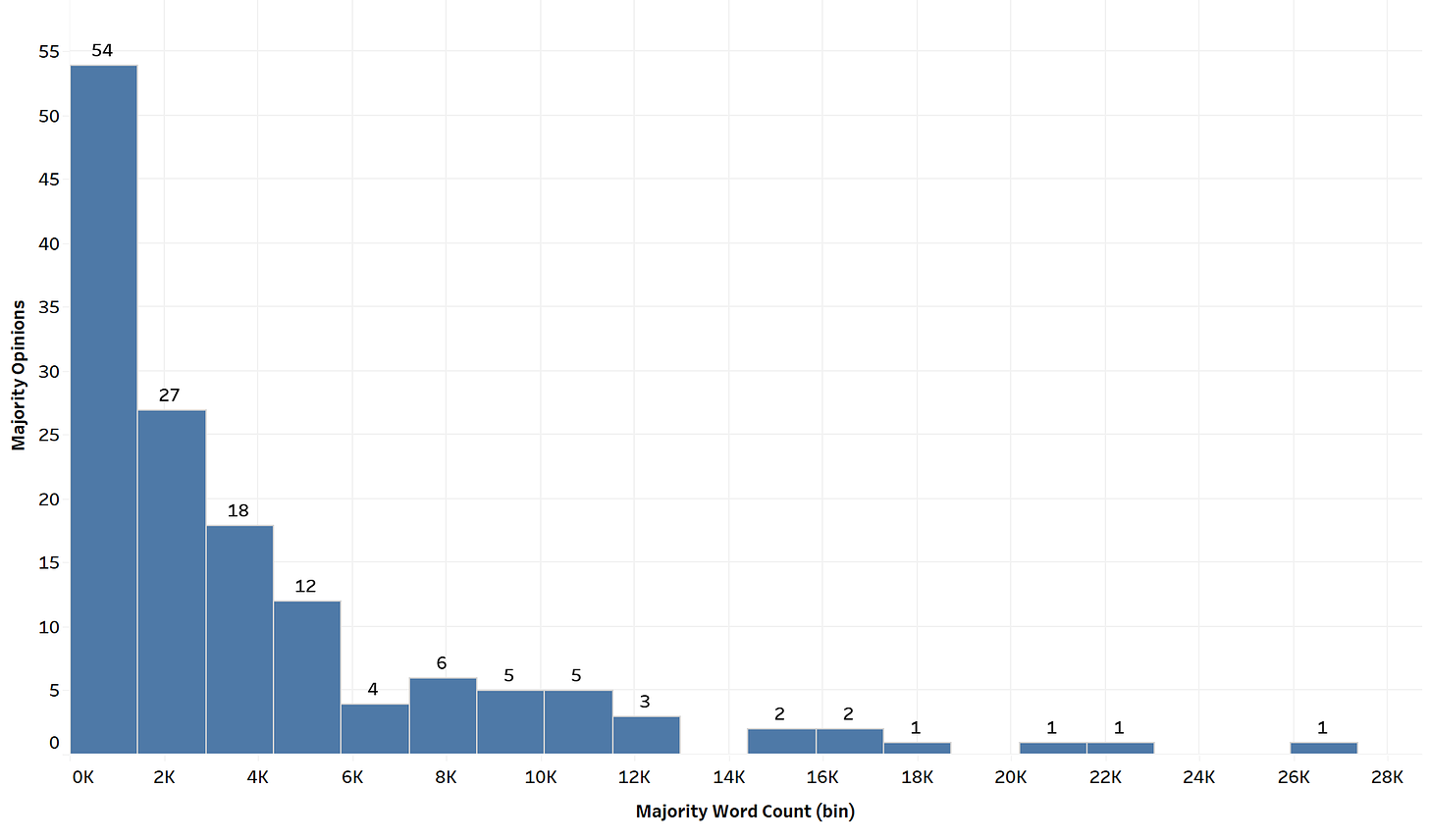

Lastly a look at opinion count based on a distribution of majority word counts.

Most of these opinions are fairly short although only six were excluded from the analyses due to fewer than 100 words in them.

I ordered this list of five cases based on relative importance, mainly on dispersed impact, but also based on the other factors I described above.

Case 1) Alliance for Fair Board Recruitment v. SEC (CA5)

Court: United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

Decision Date: December 11, 2024

Majority Opinion: Oldham; Dissent: Higginson

Issue Areas: {housing, financial, commerce, employment, liability, fraud, contracts}

Majority words count: 11,351; Dissent word count: 2,460

Amicus briefs: 14

What it’s about: This case centers around a legal challenge to rules set by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Nasdaq regarding the disclosure of certain demographic information about directors of public companies. Specifically, the rules required companies listed on Nasdaq to disclose data about the race, gender, and sexual characteristics of their directors. The plaintiffs AFBR, argued that these disclosure requirements went beyond what is allowed under the law and violated certain legal principles.

At its core, this case is about whether government regulators, like the SEC and Nasdaq, can require companies to disclose sensitive information about their directors for the purpose of promoting transparency, even if such disclosures aren’t directly related to financial performance or investor protection.

The Positions of the Two Sides:

AFBR (Petitioner):

AFBR, a group representing certain companies affected by the Nasdaq rule, argues that the SEC and Nasdaq have overstepped their authority by mandating disclosures of information that are not required by law. The main claim is that these rules go against the intent of the securities laws, which were created to protect investors from fraud, manipulation, and speculation, not to mandate social or demographic disclosures.

The group argued that requiring such disclosures doesn’t align with the goals of the Securities Exchange Act, which was primarily designed to prevent financial fraud and market manipulation, not to force companies to reveal demographic information unrelated to financial performance.

SEC and Nasdaq (Respondent):

The SEC and Nasdaq argue that their rules are within their authority and are in line with the objectives of the Securities Exchange Act. They believe that forcing companies to disclose such information is beneficial for investors and markets because it improves transparency and could potentially enhance corporate governance.

They argued that the rules are related to the Exchange Act’s goals of providing transparency and protecting investors, and that disclosing demographic data about company directors might help investors make better-informed decisions about the companies they invest in.

Key Legal and Policy Issues:

- Jurisdiction and Standing: One threshold issue in the decision was determining if AFBR had the right to challenge the rule in court. Since AFBR represented companies that were affected by Nasdaq’s rules, they had the legal standing to bring this case.

- Authority and Scope of the SEC and Nasdaq: The main legal issue was whether the SEC and Nasdaq had the authority to require companies to disclose personal demographic information about their directors. AFBR argued that this wasn’t within the scope of the securities laws, while the SEC and Nasdaq argued that the rules were related to their duties to ensure transparency in the market.

In this decision, the major questions doctrine (a current hot topic) plays a central role in limiting the scope of the SECs regulatory power over corporate governance, particularly regarding the imposition of diversity requirements on corporate boards.

Major Questions Doctrine:

The doctrine asserts that when an administrative agency, like the SEC, seeks to exercise power over a matter of significant economic or political importance, it must have clear and explicit authorization from Congress. This is because such power, if implied or unclear, could lead to significant changes in the nations economic landscape or government structure without proper democratic oversight. In this case, the SEC’s attempt to impose diversity requirements on corporate boards is seen as a “major question” due to its massive economic and political implications. In this case, The SECs action of requiring Nasdaq-listed companies to adopt board diversity policies is characterized as a “major question” because it affects the internal structures of large corporations, including those with a combined market value greater than the GDP of the United States. The court argues that, while the SEC has broad powers under the Exchange Act, it cannot claim authority to reshape corporate governance based on vague statutory provisions without clear congressional approval.

The court also highlights that this kind of regulation—pertaining to diversity on corporate boards—is traditionally handled by other agencies (like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) or state laws, not the SEC. Therefore, applying the major questions doctrine here requires skepticism of the SEC’s action, as no clear congressional mandate for such regulation exists in the Exchange Act.

Holding: Ultimately, the court concluded that the SEC’s power to regulate corporate governance did not extend to imposing diversity requirements on corporate boards, as such a measure lacks the clear congressional authorization required by the major questions doctrine.

Main points in the dissent:

- Nasdaq’s Role and SECs Limited Authority: Nasdaq, as a private company, proposed a rule (the “Disclosure Rule”) requiring companies to disclose their board diversity. The dissent argues that the SEC’s role is limited and that it is not authorized to override Nasdaq’s judgment unless the rule violates the Exchange Acts requirements. The SEC’s approval of the rule aligns with the purpose of encouraging market efficiency and investor transparency.

- Investor Demand for Diversity Information: The dissent highlights that there is substantial evidence showing that investors sought information about board composition, despite inefficiencies in how such data was previously reported. Nasdaq responded to this demand with a rule that standardizes board diversity disclosures, aiming to address information asymmetries between large and small investors.

- Disclosure vs. Quota: The dissent emphasizes that the Disclosure Rule is focused on providing information, not imposing a quota system for board diversity. This aligns with SEC’s finding that the rule is designed to remove barriers to market efficiency rather than mandate hiring practices.

- Private Experimentation and Limited SEC Intervention: The dissent defends the concept of self-regulation by exchanges like Nasdaq, which can refine their rules based on market demands. The SEC’s review should be limited to ensuring the rule doesn’t violate the principles of the Exchange Act, rather than imposing its own policy preferences.

- Consistency with Existing Regulatory Practices: The dissent notes that Nasdaq’s rule aligns with existing disclosure requirements, such as those enforced by the EEOC and SEC, demonstrating consistency with broader regulatory practices…

December 30, 2024

Originally Published in Legalytics